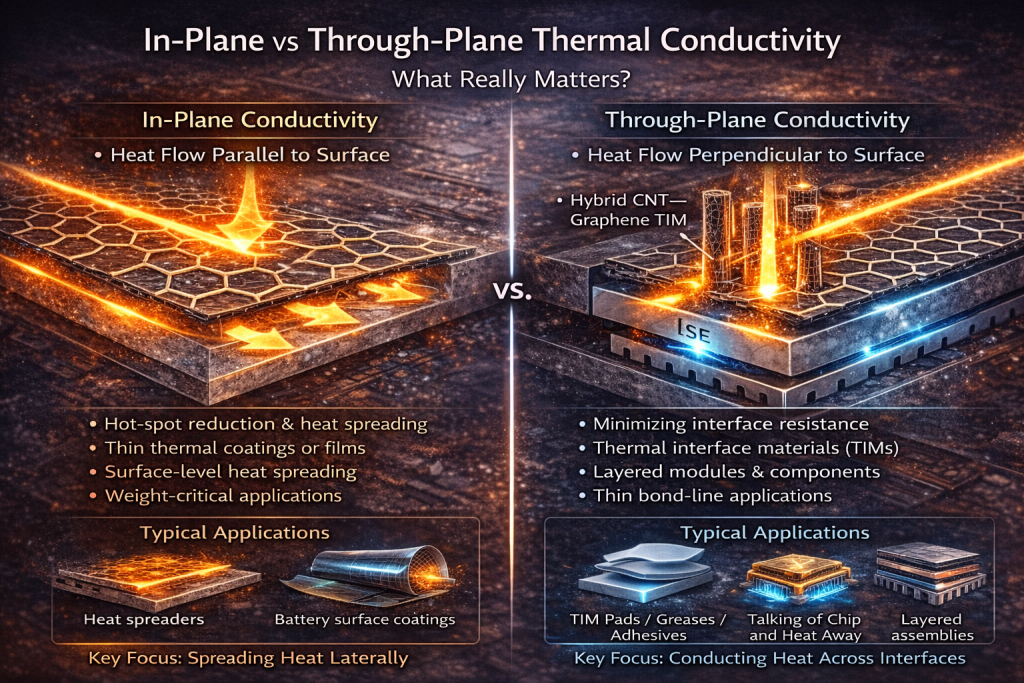

In-Plane vs Through-Plane Thermal Conductivity – What Really Matters

Why Thermal Conductivity Is Often Misunderstood

Thermal conductivity is one of the most frequently cited parameters in thermal management materials. Yet it is also one of the most misunderstood.

Many datasheets list a single thermal conductivity value, creating the illusion that heat transfer performance is isotropic. In reality, most advanced thermal materials—especially those based on CNTs, graphene, or layered fillers—exhibit strong directional dependence.

Understanding the difference between in-plane and through-plane thermal conductivity is essential for selecting the right material for real-world applications.

Defining the Two Directions of Heat Flow

In-Plane Thermal Conductivity

-

Heat flow parallel to the material surface

-

Dominated by lateral heat spreading

-

Critical for reducing hot spots

Typical measurement directions:

-

Along films, coatings, or sheets

-

Across surfaces of heat spreaders

Through-Plane Thermal Conductivity

-

Heat flow perpendicular to the material surface

-

Governs heat transfer across interfaces

-

Critical for TIMs and layered assemblies

Typical measurement directions:

-

From chip → TIM → heat sink

-

Across coatings, laminates, or stacked layers

Why Direction Matters More Than Absolute Values

A material with extremely high in-plane conductivity may still perform poorly as a TIM if its through-plane conductivity is limited.

Likewise, a material optimized for through-plane transport may fail to spread heat laterally, leading to localized overheating.

Thermal performance is not about “higher numbers,” but about matching the dominant heat flow direction.

Material Behavior by Structure

Graphene and Graphene-Based Fillers

-

Exceptional in-plane thermal conductivity

-

Limited through-plane transport due to interlayer resistance

-

Strong anisotropy

Best suited for:

-

Heat spreader coatings

-

Thin films

-

Surface temperature uniformity

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

-

Strong axial (1D) heat transport

-

Effective through-plane conduction when properly connected

-

Moderate lateral spreading

Best suited for:

-

Thermal interface materials

-

Bulk composites

-

Interface bridging

Traditional Ceramic Fillers

-

More isotropic but much lower intrinsic conductivity

-

Require high loading to be effective

-

Performance limited by particle contact resistance

Application-Driven Selection Logic

When In-Plane Conductivity Matters Most

Choose materials optimized for in-plane transport when:

-

Hot-spot mitigation is critical

-

Heat must be redistributed across a surface

-

Thin coatings or films are used

-

Weight and thickness must be minimized

Typical applications:

-

Power electronics enclosures

-

Battery surface coatings

-

LED substrates

-

Flexible electronics

When Through-Plane Conductivity Matters Most

Choose materials optimized for through-plane transport when:

-

Heat must cross interfaces efficiently

-

Bond-line thickness is small

-

Contact resistance dominates system performance

Typical applications:

-

TIMs (pads, greases, adhesives)

-

Chip-to-heat-sink interfaces

-

Layered modules

Why Single-Number Conductivity Is Misleading

Datasheet values often:

-

Average directional performance

-

Depend on measurement method

-

Ignore interface resistance

A material listed as “10 W/m·K” may perform better or worse depending on:

-

Direction of heat flow

-

Thickness

-

Interface pressure

-

Surface roughness

Direction-specific data is far more valuable than headline numbers.

Hybrid Systems: Designing for Both Directions

Modern thermal challenges often require:

-

Efficient heat extraction (through-plane)

-

Rapid heat spreading (in-plane)

This is where hybrid CNT–graphene systems excel:

-

CNTs provide vertical heat pathways

-

Graphene spreads heat laterally

-

Combined networks reduce overall thermal resistance

Such systems are increasingly used in:

-

Battery thermal management

-

High-power electronics

-

Compact and lightweight modules

Measurement and Testing Considerations

Engineers should evaluate:

-

In-plane vs through-plane conductivity separately

-

Performance at application-relevant thickness

-

Thermal contact resistance

-

Stability under thermal cycling

Blind reliance on catalog values often leads to incorrect material choices.

Design Takeaways

-

Thermal conductivity is directional, not scalar

-

Always identify dominant heat flow paths

-

Match material architecture to application geometry

-

Consider hybrid solutions when heat flow is multidirectional

Ask the Right Question First

The real question is not:

“Which material has higher thermal conductivity?”

But rather:

“In which direction does heat need to move in my system?”

By understanding the difference between in-plane and through-plane thermal conductivity, engineers can make more informed material choices—achieving better performance with lower weight, thinner designs, and improved reliability.